Woodcut Vienna from 1900

The colour woodcut in Vienna around 1900 – an “arousing experiment“[1], “the playground of artistic fantasy“[2] or a simple “decorative showpiece in the room“ with a reproducing character?[3]

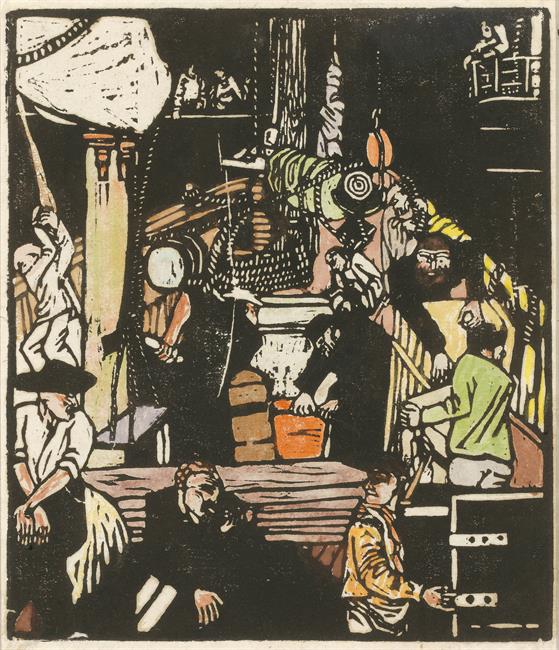

Carl Moser

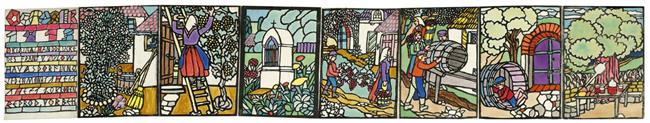

Carl Moser Franz von Zülow

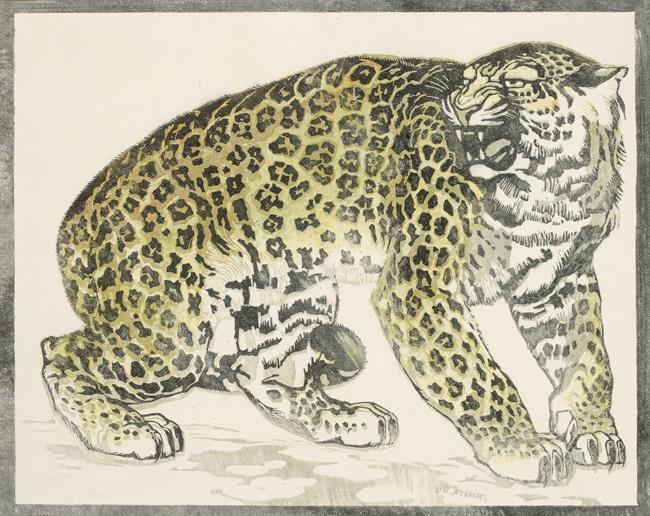

Franz von Zülow Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel

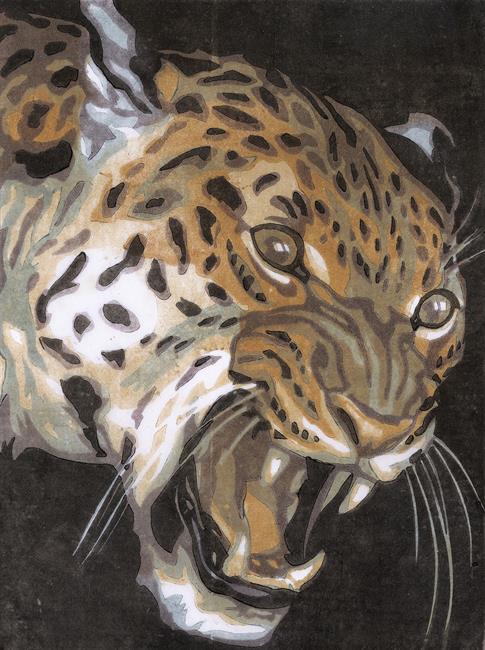

Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel

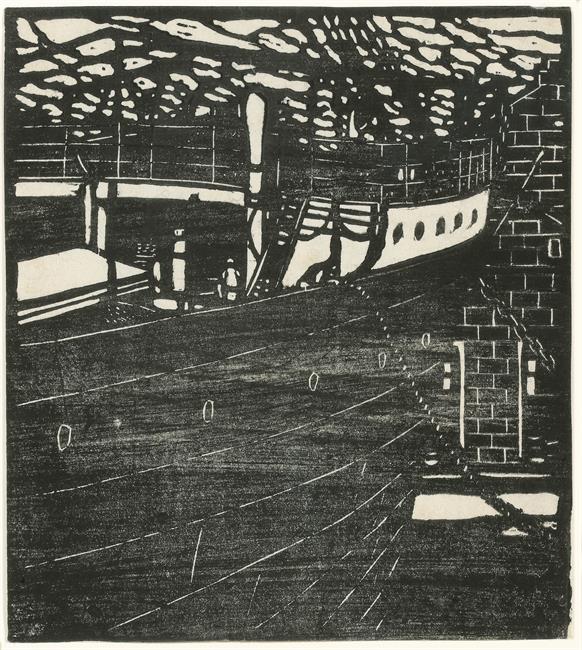

Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel Rudolf Kalvach

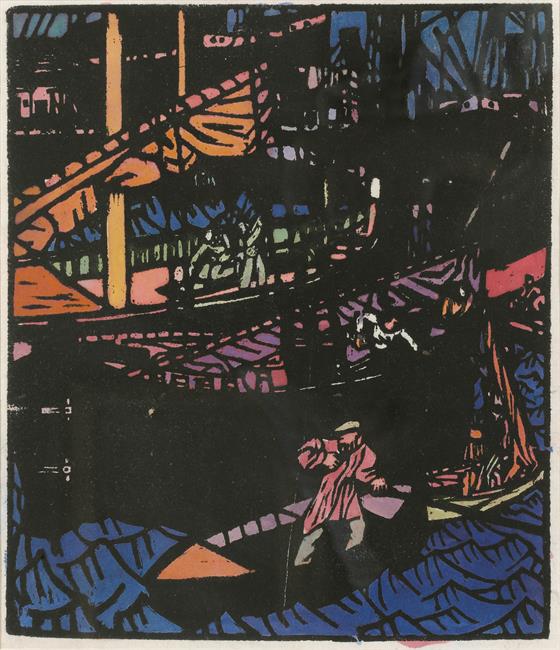

Rudolf Kalvach Rudolf Kalvach

Rudolf Kalvach Rudolf Kalvach

Rudolf Kalvach Norbertine Bresslern-Roth

Norbertine Bresslern-Roth Carl Moser

Carl MoserA decisive answer to this provocative question was given by the image of a dressing room “für ein junges Ehepaar“ (“for a young married couple“), published in the June issue of the „Dekorative Kunst“ magazine (“Decorative Art“)[1]: journalist Berta Zuckerkandl, owner of a historic Viennese salon frequented by the artistic and humanistic elite, explained the artistic principles of Kolo Moser, the co-founder of Wiener Werkstätte, using the illustrated example of an exclusive home interior. Furniture with inlays of fine woods, silken tapestries, silver lighting objects with sanded glass and stenciled murals created the adequate scope for the presentation of the portraits of the lady of the house nearby – Gertrud Löw – a painting by Gustav Klimt and a colour woodcut by Carl Moll. As an “independent work of art“[2] it is a symbol of eternal lust and the great interest in the oldest graphic reproduction technique, the incomparable creativity of their originators and, most of all, of the high appreciation for the artistic original colour woodcut in Vienna at the turn of the last century.

The woodcut looks back on a long and eventful history. After culminating in the art of the renaissance, i.e. with Albrecht Dürer, it was stuck with the nimbus of primarily being a copying and reproducing medium, until it was rediscovered by Paul Gaugin in France and Edvard Munch in Norway from 1890 onwards. Their artistic pioneer work culminated in a bloom of colour woodcut printing in Vienna around 1900, until the German expressionists, and among them, the protagonists of the Dresden based artist association “Die Brücke“ (“The Bridge“), discovered their enthusiasm for colour woodcut as a result of the reception of the original prints in the arts magazine “Ver Sacrum“, the programmatic voice of the Vienna secessionists.

Between 1900 and 1910, Viennese colour woodcut reached an unexpected bloom, which has yet to be appreciated by art reception. With the exhibition “Kunst für alle“[3] (“Art for All“) in Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Albertina Vienna, curated by Tobias G. Natter, this deficiency is clearly being leveled and the hitherto neglected subject is brought back into the focus of international exhibition activities.

The new discovery of the artistic original colour woodcut was decisively influenced by various aspects. On one hand, by the Vienna Secession, constituted in 1897 as „artistic watershed between historicism and art nouveau“[4], that not only programmatically showed the latest European art movements in its exhibition building, but also fostered the reception of Japonism in Vienna in a perspective opening across the narrow national borders. In January and February of 1900, the Secession’s VIth exhibition was dedicated to the art from the land of the rising sun. The almost 700 exhibits of religious, profanely representative and popular Japanese art from a Viennese private foundation included 150 colour woodcuts (“ukiyo-e“). The primacy of the line as the fundamental structure of the Japanese picture, pronounced surface depictions and a tendency towards black and white, subsequently defined the style. Gustav Klimt himself owned Japanese colour woodcuts, Emil Orlik passed on his knowledge about woodcut techniques, which he had acquired during a lengthy stay in Japan, in classes after his return in 1902.

The “Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs, Secession“ (“Union of Austrian Artists, Secession“) played a significant part in Vienna’s pioneering role as “Tummelplatz für die graphischen Künste“[5] (“playground of the graphic arts“) – not only due to its progressive exhibition activities in the so-called “Tempel für die Kunst“ (“temple for the arts“), built by Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1897-1898 and controversially discussed by the public, with its iconic golden cupola (“Krauthappel“), but also due to the publication of their own arts magazine with the pioneering title “Ver Sacrum“ – “Holy Spring“. After all, 216 graphic artworks – designated “original woodcuts“ – were published in “Ver Sacrum“, the Secession’s official union organ, during the magazine’s last two years 1902 and 1903.

Along with the Secession, the Kunstgewerbeschule (“school of applied arts“) undeniably held its ground as the second centre of the Wiener Moderne (“Viennese Modern Age“). Felician Freiherr von Myrbach, who had worked as an illustrator in Paris for many years, was appointed professor at the graphic department of the Kunstgewerbeschule. Later, during his directorate between 1899 and 1905, the school would be re-positioned. Von Marbach carried out numerous staff turnovers, filled apprenticeship openings primarily with members of the Secession and installed workshops that guaranteed practical training in all artistic techniques. Besides – in contrast to the Akademie der bildenden Künste (“Academy of Fine Arts“) –, female students had been admitted since the school’s foundation in 1867. Under the aegis of Kolo Moser and Alfred Roller, both teachers at the Kunstgewerbeschule since 1899, Moser in the “master class for decorative drawing and painting“, Roller in the general department and in the department for figurative drawing, the Vienna colour woodcut was starting to flourish.

In 1905, after the so-called Klimt group had withdrawn from the Secession (including Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser, Otto Wagner and Carl Moll), the printmakers were cooperating with the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna’s workshops), founded by Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser and the industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer in 1903, and the Vienna based Galerie Miethke. The close link between the colour woodcut in Vienna around 1900 and Wiener Werkstätte existed from a formal-aesthetic point of view, as well as in terms of manpower: thanks to their teachers Josef Hoffmann and Kolo Moser, the most talented students of the legendary Kunstgewerbeschule obtained lucrative orders from Wiener Werkstätte. At the same time, Carl Moll, in his function as artistic director of Galerie Miethke, featured the most important protagonists of Vienna colour woodcut in temporary exhibitions: Rudolf Kalvach, Broncia Koller-Pinell, Carl Moser, Franz von Zülow or – Carl Moll.

These different evolutionary strands were skillfully bundled in 1908, in the scope of Klimt group’s “Kunstschau“ (“Art Show“) on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of Emperor Franz Joseph’s ascension to the throne. “At the art show in 1908, colour woodcut experienced the most beautiful gathering“[6]. “Thus, in 1908, Wiener Kunstschau presented a who is who of Viennese colour woodcut unlike ever before or after: […] Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel, Rudolf Kalvach, Broncia Koller-Pinell, Carl Moll, Carl Moser […], Franz Zülow […] and others.“[7] In his opening speech, Gustav Klimt voted for an “extended concept of art“, the negation of the differentiation between high and applied art, on the other hand, lead to a clear plea for the upgrading of graphic print in general and the colour woodcut in particular.

The most famous and original creations of the artistic original colour woodcut in Vienna emerged from the combined roles of a painter, a woodcutter and a print worker – the ideal of the so-called “peintre-graveur“. In Japan, however, the classical organization for the woodcut production stipulated a division of labour between at least three, possibly even four parties (including the publisher). For his elaborate colour woodcuts, Carl Moser, who must be mentioned as an example here, time and time again adjusted the printing blocks, added or removed panels and made use of the effects of colour in a virtuoso manner.

Style-defining principles of the colour woodcut in Vienna, which advanced the evolution of modern imagery at the beginning of the 20th century, were a new sensitivity towards the beauty of the line, the delicate ponderation of weights (e.g. large, empty coloured areas contrasting with abundantly ornamented zones: the principle of the “empty area”), a tendency towards closed colour compartments and strict geometrisation and the knowledge of stylisation of areas.

Thematically, the artists recurred to landscape motifs drawn from their immediate surroundings (think of Carl Moll’s views of Vienna), whereas depictions of persons played a subordinate role. Also rarely to be found are sheets depicting scenes of everyday or working life (exception: Rudolf Kalvach’s woodcuts of Trieste’s port life). Elements of an eccentric, exuberant fantasy, originating in the realm of the “grotesque”, found their natural entry into the repertory of motifs (see Jungnickel’s colour woodcut “Rauchende Grille” [“Smoking Cricket], erroneously entitled “Rauchender Ziegenbock” [“Smoking Billy Goat“]).

“Striking in the matter of the colour woodcut in Vienna is the choice of themes drawn from the animal kingdom”[8], states Tobias G. Natter. Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel distinguished himself throughout his life by creating pictures of animals in an array of techniques. He presented his first colour woodcuts at the 1908 Vienna Kunstschau. A significant feature of Jungnickel’s animal depictions is the rendition of animal motifs paired with human characteristics and mental states he repeatedly aimed for. A pronounced preference for animal pictures can also be identified several years later in Norbertine Bresslern-Roth’s work, who excels with distinctive, emphatic observations of animals, using linocut technique, a variant of woodcut. From October 25, 2016 thru April 17, 2017, Neue Galerie Graz honors this outstanding artist with a solo exhibition.

Examples of the artistic techniques appropriate for woodcuts include Ludwig Heinrich Jungnickel’s stencil spray technique (omitting contour lines), Norbertine Bresslern-Roth‘s linocut, with the soft and smooth material’s pore-free surface enabling a uniform application of colour, and Franz von Zülow’s paper–cut printing. In 1907, Zülow obtained the patent for this less exhaustive printing technique that he had developed in 1903, using a blackened hard paper stencil for printing the cut-out areas and bridges rather than for transferring the outlines like in woodcutting.

In a letter to his mentor, the art writer and critic Arthur Roessler, Egon Schiele expressed his ambivalent attitude towards graphic printmaking: “I know from colleagues that graphic works sell more easily than paintings, particularly if the dimensions of those latter ones go beyond the popular ‘Decorative Showpiece Format’. As much as I’m tempted to do graphic work – and not only for the easier sale – but neither do I know how to etch nor to cut in wood, and I lack the patience to learn this technique. For in the time I need to do an etching on a plate, I can easily draw fifty to sixty, even more, certainly close to a hundred sheets.”[9]

Andrea Schuster

[1] B. Zuckerkandl: “Koloman Moser”, in: Dekorative Kunst (Decorative Art), vol. 12, Munich 1904, p. 329-345, here: p. 332

[2] cf. Max Bucherer and Fritz Ehlotzky: Der Original-Holzschnitt. Eine Einführung in sein Wesen und seine Technik (The Original Woodcut, An Introduction to its Nature and Technique), Munich 1914, p. 36

[3] The exhibition “Kunst für alle. Der Farbholzschnitt in Wien um 1900” (“Art for All. The Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900“) will be held at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt from the 6th of July until the 3rd of October 2016, before moving to Albertina Vienna from the 19th of October 2016 until the 22nd of January 2017.

[4] Tobias G. Natter: “Die Blüte des Farbholzschnitts in Wien um 1900. Meilensteine und Vielfalt seiner Entwicklung“ (“The Bloom of Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900. Milestones and Diversity of its Evolution“), in: exhibition catalogue “Kunst für alle. Der Farbholzschnitt in Wien um 1900“ (“Art for All. The Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900“), Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Albertina Vienna 2016-17, p. 12-32, here: p. 15

[5] Karl M. Kuzmany: “Jüngere österreichische Graphiker. II: Holzschnitt“ (“Younger Austrian Graphic Artists. II: Woodcut“), in: Die Graphischen Künste (The Graphic Arts), year 31, Vienna 1908, p. 67-88, here: p. 69

[6] Tobias G. Natter: “Die Blüte des Farbholzschnitts in Wien um 1900. Meilensteine und Vielfalt seiner Entwicklung“ (“The Bloom of Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900. Milestones and Diversity of its Evolution“), in: exhibition catalogue “Kunst für alle. Der Farbholzschnitt in Wien um 1900“ (“Art for All. The Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900“), Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Albertina Vienna 2016-17, p. 12-32, here: p. 24

[7] idem, p. 23

[8] Tobias G. Natter: “Die Blüte des Farbholzschnitts in Wien um 1900. Meilensteine und Vielfalt seiner Entwicklung“ (“The Bloom of Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900. Milestones and Diversity of its Evolution“), in: exhibition catalogue “Kunst für alle. Der Farbholzschnitt in Wien um 1900“ (“Art for All. The Colour Woodcut in Vienna around 1900“), Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and Albertina Vienna 2016-17, p. 12-32, here: p. 27

[9] Otto Kallir: Egon Schiele. Das druckgraphische Werk (Egon Schiele. The Print Oeuvre), Vienna 1970, p. 14