-

Gunter Damisch

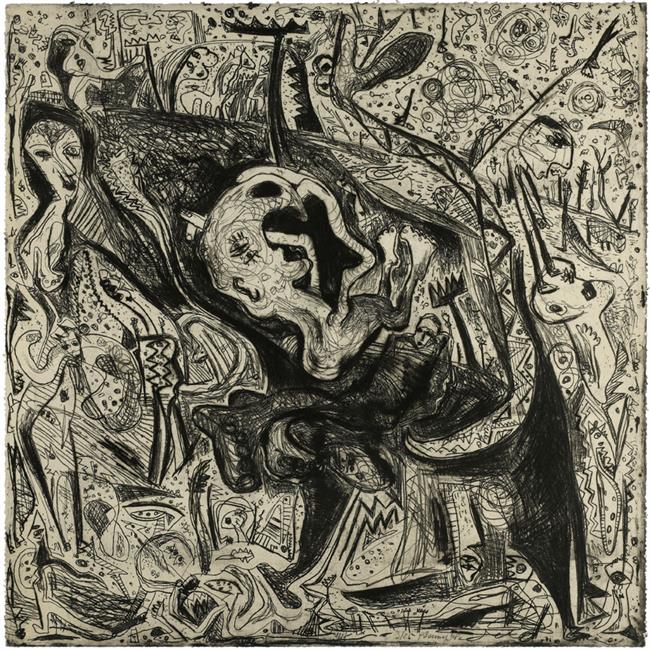

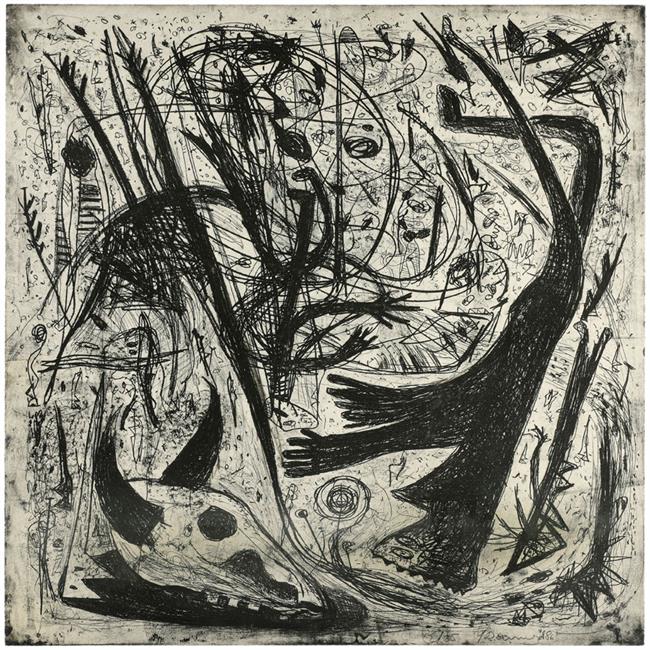

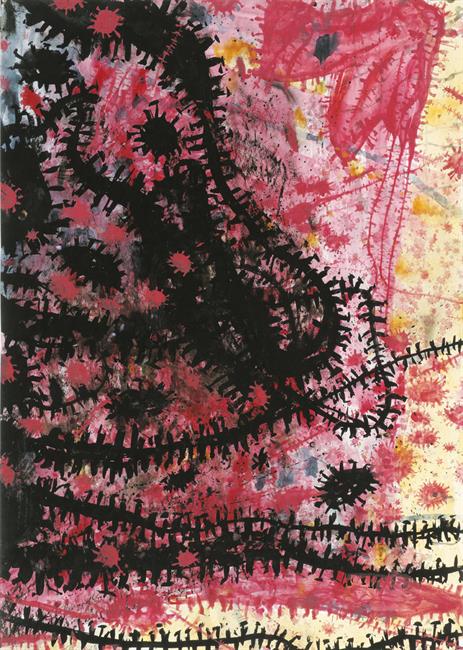

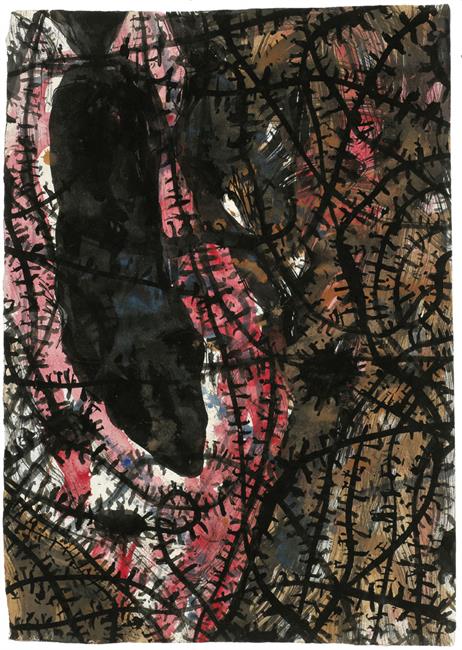

Untitled 1986Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1986Gunter Damisch

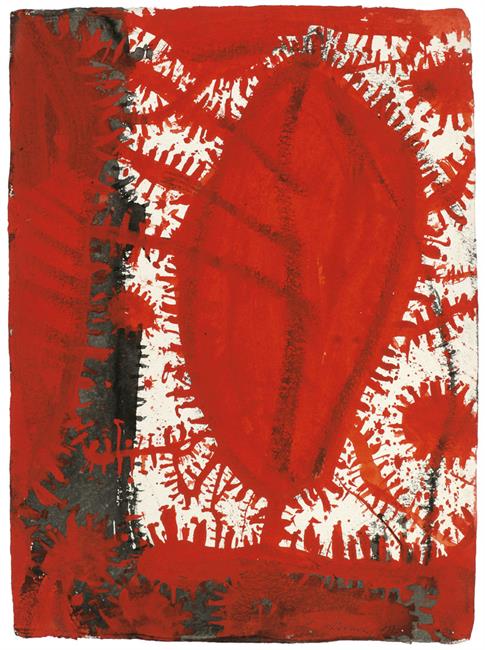

"Rotweltmorgen" 2004 -

Gunter Damisch

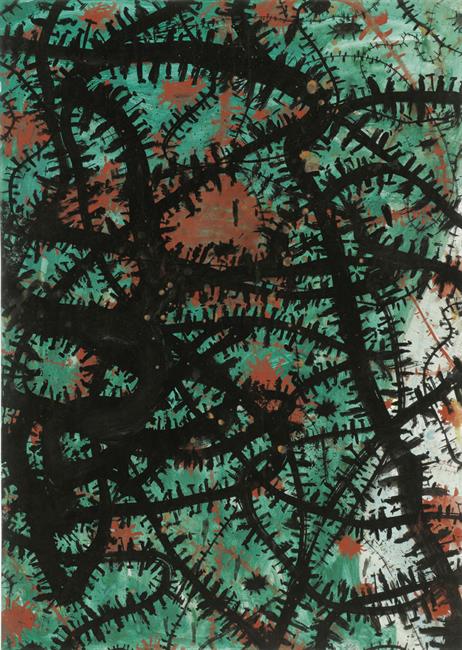

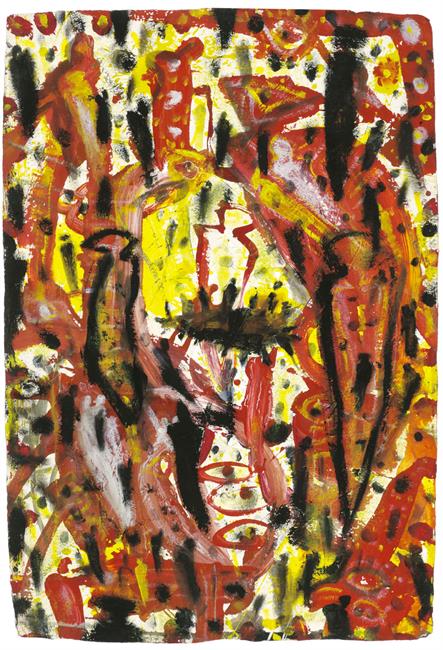

"Nachtflammenort" 1998-99Gunter Damisch

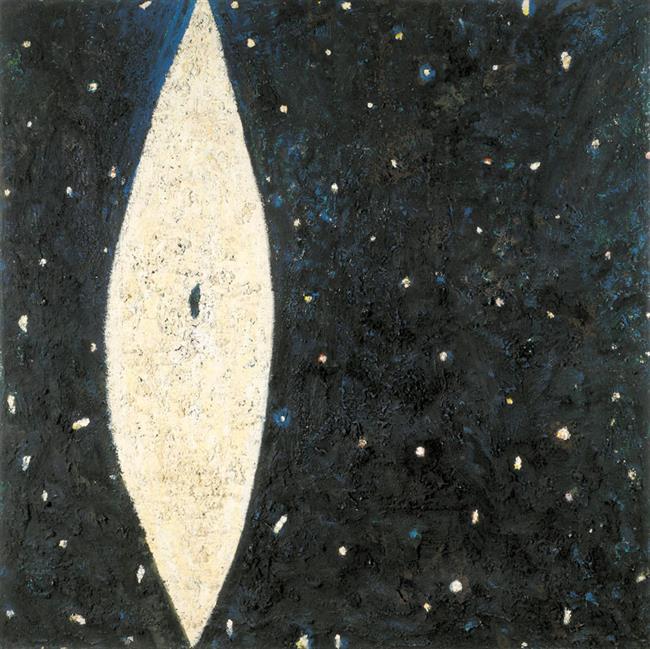

"Blaufeldsteher" 1990-91Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1998 -

Gunter Damisch

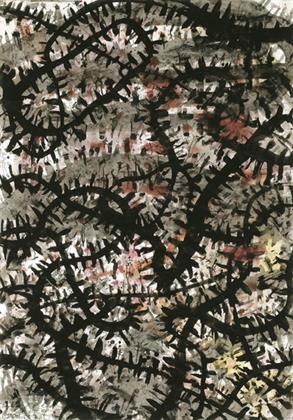

Untitled 1998Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1998Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1997 -

Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1999Gunter Damisch

Untitled 1999Gunter Damisch

"Weltplatz" 1992

Gunter Damisch – “Cosmic Gardens”[1]

Gunter Damisch, one of the most important representatives of contemporary art in Austria, died much too early on the 30th of April 2016 in Vienna. Attributes such as charismatic artistic personality, amiable person, brilliant teacher, passionate gardener, fervent collector, staunch humanist, are merely a selection of purely subjective ways to––rudimentarily––capture a universal and artistically versatile character striving for “complexity“ and “diversity“[2]. Our exhibition tries to document the artistic range, creative power and stylistic wealth of Gunter Damisch’s comprehensive oeuvre with a top-class selection of his work and a clear focus on his works dating from around 1990 as a sort of pars pro toto.

Gunter Damisch was a multimedia artist: oil paintings were on a par with paper works, graphic reproductions, collages, ceramics, bronze or aluminium castings. Common to all exhibits is their inherent processual component. Hence, in an interview in 2008, Gunter Damisch emphasised: “The processual aspect is important to me. On the one hand, there is the painting process. […] On the other hand, I am fascinated by the processual aspect as such. ‘Field‘ [an essential term in his consistently refined repertory of forms], for example, is a processual term used in sociology, physics and natural sciences.“[3]

Gunter Damisch’s individual, open, modular image system, staged in an improvised manner, is substantially based on the concept of transition and metamorphosis; panta rhei, everything flows, the view through an artistic microscope or the camera, his movement; zooming equally allows for distant and close-up view or the macro and microcosmic. Energetic concentrations, organic natural forms, vibrant kinetic energy, mineralogical concentrations, astronomic protuberances organise a very personal system of a visual world, characterised by emphasis, creative desire and impulsive dynamic. In this context, terms such as “field“, “world“, “path“, “networks“, “stayers“, “flimmers“, “streaming“, “flowing“ or “flickering“ are imperative.

“Painting equals casting nets in the sea of consciousness.”[4] As part of the second generation of the Austrian artist group “Neue Wilde“ (“Wild Youth“)––together with Alfred Klinkan, Hubert Scheibl, Gerwald Rockenschaub, Otto Zitko or Herbert Brandl, with whom he shared a studio for a few years––, Gunter Damisch’s painting practice of the 1980s is determined by a pasty, layered, clotted, inhomogeneous, heavily encrusted, smeary application of paint that could almost directly be experienced as a painting substance itself, and which generated a haptic, sometimes nearly “archaic“ overall work. From 1986-87 onwards, almost monochrome image compositions, i.e. “fields“, were complemented by small islands of different colour, i.e. “worlds“. These are populated with amorphous figural ciphers, “stayers“, “headers“ or “flimmers“ whose basic principle was verbalised by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in “The Little Prince“[5]. While at first, the figures are depicted standing upright, they later on circulate in all directions. “The early form were the heavy stayers anchored to the floor, whose head-shapes only needed to be implied in order to be read as figural cypher. In a next step, I created figures defying gravity that hardly disposed of extremities and seemed to be floating––figures that are to be found in a floating, flowing system. These are the flimmers, which in the sense of the term are rather gaseous creatures––the connectors between the worlds. […] In a final work period, figures were also composed of figures––often, the single figure can hardly be read.“[6]

Meandering, linear elements are inscribed in Gunter Damisch’s limitless cosmic pictorial spaces; convolutions, networks and knots that refer to a circular habitus and bear the artistic expression of solidification. These bow- and loop-like brushstrokes refer back to Tibetan or Asian examples such as the infinity symbol (ditto to the fish symbol), as well as to the Gordian Knot, ornaments of the Renaissance or Jackson Pollock’s “drippings“.

“Lattice-like, movements and lines and their touch points form a web, interlinked lanes and pathways cross and join, the spaces are arranged in winding circles towards each other, growing together on the touch points and forming inner places and cavities with vistas according to the Swiss cheese method, figure-covered gaps and niches turn into protected zones and cells. […] These [linear] forms are owed to the worms and snakes, slings and lianas, creeks and meandering rivers, shorelines and watersides, rivulets and worm damage cavities, the traces of beetle damage in barks and the erosion of the waters […]”[7]

In a congenial manner, lyric, metamorphic image titles that are solely descriptive and whose primary purpose is to file and identify his works, correspond to the complex, polymorphic, so to speak archetypal repertory of forms of the “painter poet”[8] Gunter Damisch. In this context, Damisch preferred a playfully open, associative approach to a lecturing one; quite naturally, the beholders of his paintings are encouraged to find different explanatory models and titles for his artistic manifestations that constantly undergo permutations and to “make the opening perceptible as an opening“[9].

In the mid-1990s, Gunter Damisch ambitiously attempted to equalise the pasty, archaic-looking, concentrated conglomerates of paint constructed in layers, with the “swallow’s nest technique“––a term used by Herbert Brandl. He would attempt to liquefy the paint and to create versatile painted movements in space and time, of a sculptural character and in an intricate ornamental order through a precisely calculated use of trickling, dripping paint on a sophisticated background.

Gunter Damisch explicitly traced the clear chromatic vitality of his paintings on canvas and paper. “I am much rather searching for the strong contrasts in order to create tensions and to place the formulations”[10], the artist stated in 2011.

Besides the art of painting, the drawing as an equitable medium and a conscious graphic “notation“ claimed an adequate position in Gunter Damisch’s universal imagery. Biographically knowledgable thanks to his studies in Max Melcher’s master class for graphic art and his more than 20 year long teaching assignment as professor for graphic art and graphic reproduction techniques at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, his rhizomatic structures, lava-like, floating streams of colour, rhythmic serpentine lines, vortices, slings and monads constituted a generally accessible emblematic and morphology of symbols. Complementarily to his paintings and graphic works, he had been creating sculptures since the 1980s. At first, they would resemble totems, colourful, expressive, executed in a relatively crude manner, in the tradition of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s wooden objects. These colourful, carved woods were then replaced by dark, perforated and hollowed wooden planks with stayers, flimmers, slings and worlds. Simultaneously, Gunter Damisch built jagged, pointed, rough, partly sphere-like bronze sculptures in the old casting technique of the lost form. The bronzes, apostrophised by Otto Breicha as “spiky models for the world as a whole“, often consciously designed with cavities, reference the artist’s lively fascination for mineralogy and geology. Creatures that have shrunk down to symbolic tininess are bustling in Damisch’s “inner places“ as well as on the margins. Scaffolds and delicate, larger than life, reticular towers with poured-off finds of cones, dried out sunflowers, parts of ornamental pumkins, stems of evening primroses or snail shells, to name but a few, and an appropriate population of stayers, ultimately complete Damisch’s sculptural shape vocabulary. In this context, Peter Weiermair underlined Gunter Damisch’s “dialogue with nature“ and compared his “bronzes inscribed in the air“[11] with “petrifications from the distant memory of our present day flora”[12]. Since 2002, Damisch increasingly used cast aluminium for his spatial works. He accentuated the colour of his sculptures using acids as well as varnish.

In a conversation that was published later on, the “painter poet”[13] Gunter Damisch, who had spent a few semesters studying medicine, German philology and history, concluded: “it is a beautiful thought that [art] can be somewhat of a massage for the neurones, an occasion to reach the non-static state [i.e. the opposite of the static conception of good and evil] with open eyes; a dance-like perception of oneself as the perceiver.”[14]

Andrea Schuster

[1] cf. Wolfgang Drechsler, “Kontinuität und Wandel. Zur Malerei von Gunter Damisch“ (“Continuity and Transformation. The Paintings of Gunter Damisch“), in: exhibition catalogue “Gunter Damisch. Aus dem Weltengarten“ („Gunter Damisch. From the Garden of Worlds“), Landesgalerie Oberösterreich, Linz 1998 and Kunsthalle Emden 1999, p. 7-20, herein: p. 18

[2] Sabine B. Vogel, “Kunst als Massage der Nervenzellen – Gunter Damisch im Gespräch“ („Art as Massage of the Neurones––A Conversation with Gunter Damisch“), in: Gunter Damisch, Weltwegschlingen. Drawings / Paintings 1997-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 6-19, herein: p. 16

[3] Interview with Gunter Damisch, 8th of May, 2008

[4] Gunter Damisch, in: exhibition catalogue “China retour. Im Osten geht die Sonne auf, im Westen auch“ (“China Return. The Sun Rises in the East and in the West, too“), Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna 2005-06, p. 158

[5] Interview with Gunter Damisch, 8th of May, 2008

[6] Sabine B. Vogel, “Kunst als Massage der Nervenzellen – Gunter Damisch im Gespräch“ („Art as Massage of the Neurones––A Conversation with Gunter Damisch“), in: Gunter Damisch, Weltwegschlingen. Drawings / Paintings 1997-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 6-19, herein: p. 8

[7] Gunter Damisch, “Unschlüssige Schlingen“ (“Indecisive Slings“), in: Gunter Damisch, Weltwegschlingen. Drawings / Paintings 1997-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 20-23, herein: p. 20

[8] Dieter Ronte, “Köstliche und erlesene Früchte“ (“Delicious and Exquisite Fruits“), in: exhibition catalogue “Gunter Damisch. Malerei. Skulptur“ (“Gunter Damisch. Painting. Sculpture“), Museum Folkwang, Essen 1991-92, [no p.]

[9] Sabine B. Vogel, “Kunst als Massage der Nervenzellen – Gunter Damisch im Gespräch“ („Art as Massage of the Neurones––A Conversation with Gunter Damisch“), in: Gunter Damisch, Weltwegschlingen. Drawings / Paintings 1997-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 6-19, herein: p. 18

[10] ibid., p. 14

[11] Peter Weiermair, “Überlegungen zu den Zeichnungen von Gunter Damisch“ (“Thoughts on the Drawings by Gunter Damisch“), in: Gunter Damisch, Skulpturzeichen. Zeichnungen (Sculpture Symbols. Drawings) 2006-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 6-9, herein: p. 6

[12] ibid.

[13] cf. note 8

[14] Sabine B. Vogel, “Kunst als Massage der Nervenzellen – Gunter Damisch im Gespräch“ („Art as Massage of the Neurones––A Conversation with Gunter Damisch“), in: Gunter Damisch, Weltwegschlingen. Drawings / Paintings 1997-2010, Hohenems and Vienna 2011, p. 6-19, herein: p. 18